Inherited Power, Uncertain Future: How Lineage is Reshaping Politics in J&K

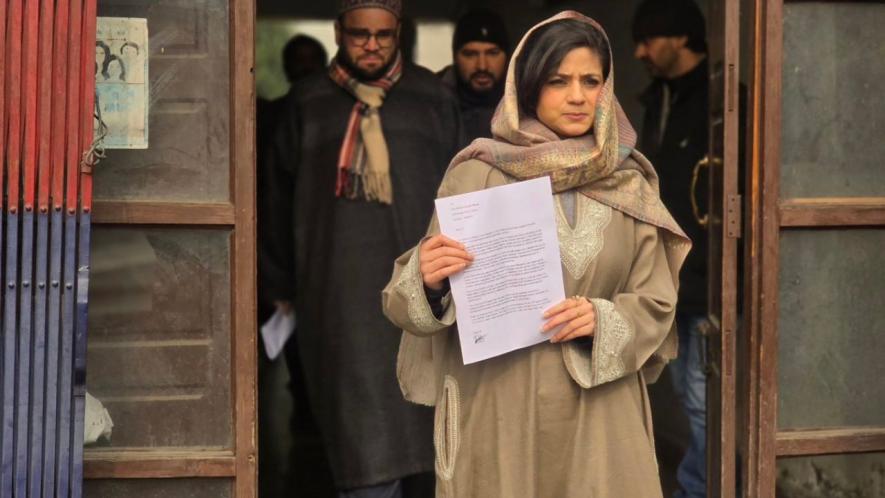

Image Courtesy: Twitter/@IltijaMufti

The political landscape of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) is entering a new and uncertain phase. The 2024 Assembly elections revived democratic participation after years of institutional suspension, yet these simultaneously exposed an old dilemma: the steady rise of hereditary politics. With National Conference leader Omar Abdullah’s sons stepping into public life, Iltija Mufti (Mehbooba Mufti’s daughter) assuming a central position in the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), and Engineer Rashid’s brother gaining prominence, one must ask: Are we witnessing democratic renewal, or merely a generational recycling of political families? The question is not whether these individuals have the right to contest, they clearly do, but whether political office in J&K is slowly being treated as an heirloom rather than a responsibility earned through public trust.

Dynastic politics is not unique to Jammu and Kashmir, nor is it inherently illegitimate. But does a region that has lived through conflict, disenfranchisement, and fractured political institutions, not require a deeper, more open democratic ethos? When leadership is transferred through bloodlines, does it strengthen or diminish the moral authority required to represent a politically sensitive society?

Jammu and Kashmir has historically produced leaders who rose not from family privilege but from the hard labour of public engagement, teachers, trade unionists, poets, social workers. What happens to this tradition when inheritance becomes the primary route to leadership?

Elite theorists, such as Vilfredo Pareto and Gaetano Mosca, remind us that every society is governed by a small group that instinctively seeks to preserve itself. If this instinct is universal, what distinguishes a democracy from an oligarchy? It is the openness of circulation, the capacity for new leaders to emerge, challenge, and eventually replace old elites. If political families in the Valley increasingly rely on lineage to retain influence, what space remains for young professionals, activists, and first-generation politicians who wish to enter public life? Is elite renewal even possible when parties prefer the safety of familiar surnames over the uncertainty of new voices?

Hereditary politics does not merely shape candidacies; it shapes the imagination of politics itself. It subtly conveys that leadership is not fully tied to merit, struggle, or service but to genealogical continuity. When parties present family members as natural inheritors of political authority, can we still claim that democratic values guide political selection? Even more importantly, does the legacy of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah or Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, impactful as they were, entitle their descendants to govern indefinitely? If historical contribution alone becomes a political passport for future generations, does democratic legitimacy not weaken at its roots?

It is important to acknowledge that no single institution, neither the Central government nor regional political parties, determines the fate of democracy in J&K. The region’s political future is shaped by a web of expectations, institutional reforms, anxieties, and memories. But this raises a deeper question: Is democratic revival merely about holding elections, or is it about reclaiming the spirit of accountable and inclusive representation? Minimising the role of a dynasty is not about excluding anyone; it is about ensuring that political office is accessible to those who earn public trust, not only those who inherit influence.

The post-2019 moment has often been described as a phase of rebuilding. Yet, while governance structures have sought to create new spaces of participation, political parties have frequently turned inward, relying on established family networks rather than widening their base. What does this combination, administrative restructuring from above and dynastic consolidation from below, mean for democratic possibility? Does it produce a more vibrant polity, or one caught between continuity and closure?

No group feels this more acutely than the youth of Jammu and Kashmir. For a generation that has grown up amid uncertainty and limited opportunities, hereditary politics reinforces a troubling perception: that political structures are not accessible to ordinary citizens. If young people see leadership as something passed down within a few families, why would they imagine politics as a space where their own energies matter? And if politics does not speak to their aspirations, who will represent the future of the Valley?

What Jammu and Kashmir needs today is not the elimination of political heirs but the expansion of political horizons. Can parties embrace internal democracy that promotes talent beyond lineage? Can civil society cultivate a culture where public service is valued over family name? And perhaps most crucially, can citizens themselves demand a politics that mirrors their aspirations rather than their memories?

Jammu and Kashmir stands at a defining juncture. Elections have returned, but elections alone cannot guarantee democratic renewal. Hereditary politics may provide comfort in a time of uncertainty, but comfort should not be mistaken for transformation. The crucial question is whether the region can move beyond inherited authority toward a more inclusive, transparent, and merit-based political culture. If the Valley is to reclaim its democratic vitality, it must resist the quiet normalisation of the dynasty and allow a new generation of leaders, untethered to family legacy, to emerge.

Ultimately, democracy is not only about who governs but about how society imagines leadership. Will Jammu and Kashmir choose the familiarity of lineage or the possibilities of renewal? The responsibility lies not just with political parties but with the public itself, to question, to engage, and to insist that leadership be earned, not inherited. Only then can the region hope, not merely to return to electoral politics but to revive the deeper democratic spirit that sustains a just and representative society.

The writer teaches Political Science at Akal University, Punjab. The views are personal. He can be reached at [email protected]

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.