In South Andamans District, Crocodiles Crawl Out After Floods

Port Blair, Andaman and Nicobar: As the heavy rains that battered South Andaman district in late September eased slightly, Navin Halder (35) set out one morning to fetch coconuts. His routine required him to cross the Guptapara Fish Landing Centre (FLC), a designated site where fishing boats unload and auction their catch, located about 25 kilometres from Port Blair, to reach a patch of land flanked by two creeks.

Along with a coworker, Navin usually plucked coconuts in the early hours and carried them on their backs to the market. But that morning, the presence of an unexpected visitor stretched their work until noon.

“We didn’t notice the crocodile at first,” Navin told 101Reporters. “I was plucking coconuts with my bamboo stick and my coworker was collecting the fallen ones. We know there are crocodiles in the creek, but they never came up, so we hardly looked around. While he was picking the coconuts, I saw the crocodile close to him and asked him to move away fast. We had no idea they could climb up to such heights.”

Navin lives in Guptapara, a village in the district. Like many creekside settlements across the islands, Guptapara has been witnessing more frequent crocodile sightings in recent years, sometimes far beyond the waterways where the animals were once largely confined.

Crocodiles, Conservation and Conflict

Saltwater crocodiles are apex predators, capable of taking down almost anything in their path. But there was a time when they were prey too. Until the mid-1900s, Andaman’s saltwater crocodiles, known as “salties”, were hunted extensively for their skin and eggs, or killed as pests, pushing the population close to extinction.

Their numbers began to recover after they were granted legal protection under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Restrictions on mangrove cutting introduced in the 1980s further helped restore estuarine habitats critical to crocodile survival. Today, forest department estimates and conservation studies put the crocodile population in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands at around 400-500.

While officials describe this as a conservation success, residents living along creeks say they are increasingly bearing its costs.

“We used to fish in neck-deep waters earlier, but now we are afraid to enter even knee-deep water,” said V Karuppuswamy (40), a fisherman at the Guptapara fish landing centre. “A crocodile once came right next to my boat at night. It takes dogs straight from the jetty. This wasn’t seen earlier. We have been seeing this more over the last ten years.”

Similar accounts are common in Guptapara. Residents said crocodiles are now appearing in smaller streams and in areas where they were rarely seen earlier, moving beyond the main creeks and closer to jetties, fields and homes.

“Crocodiles were not present in all these streams earlier,” said Navin Halder. “Over the last eight to ten years, they have been seen more. They come to eat the leftover bait thrown near the jetty. Once they come up, they stay. Two or three years ago, one even came behind my house.”

Many residents attribute the increase in sightings to food waste entering the creeks. Fishermen said discarded bait and fish waste attract crocodiles, but argued that this has only intensified an already existing problem.

“If waste is being dumped in the creeks, everyone does it,” said Kumud Ranjan Saojal, a resident of Guptapara. “Why blame only fishermen? Earlier there were fewer people here. Now there are more people dumping meat waste into the creeks, so the crocodile will obviously come.”

Residents acknowledge that waste plays a role, but say it intersects with deeper ecological and demographic shifts.

Some fishermen also allege that crocodiles captured near settlements are released into the open sea rather than kept in captivity, from where they eventually swim back. According to them, such animals, accustomed to human-associated food sources, return repeatedly to areas close to settlements.

Forest Officials Reject Claims

“Whenever a crocodile is captured, it is kept at the Chidiyatapu Biological Park,” said Sanjay Kumar Sinha, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests. “We are currently feeding around 80 crocodiles there. Even if crocodiles had been released into the sea in the past, incidents would be concentrated in one area. Instead, sightings are spread out. We also have records of crocodile attacks dating back to the early 2000s, it is not a new issue.”

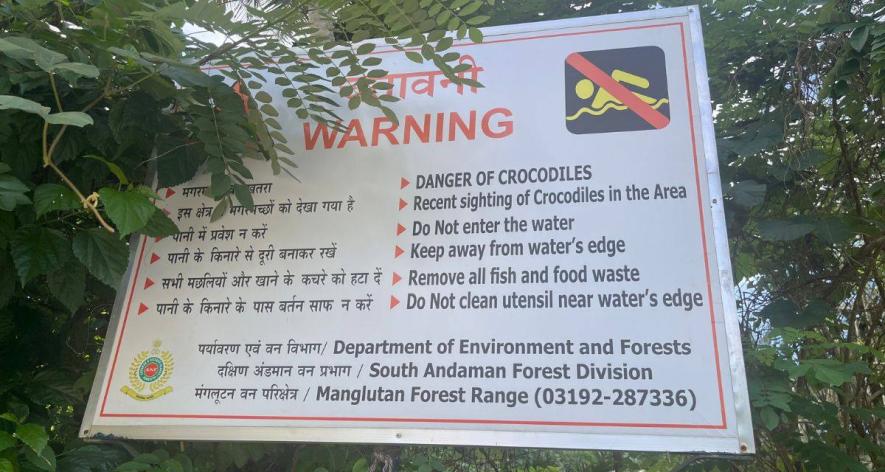

According to Sinha, official records show 22 crocodile attack incidents since 2002. “Earlier, there used to be three to four attacks annually. In fact, attacks have reduced over the last two to three years. There has been no incident in the past three years. Awareness has increased, warning signboards have been installed, and we are capturing more crocodiles. This year alone, I have issued 25 capture orders, and 13 crocodiles have already been caught,” he said.

Meera Oommen, a trustee of the Dakshin Foundation and the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust, said waste disposal near creeks is one of several factors driving human-crocodile conflict in the Andamans. She pointed to the species’ natural behaviour as another key reason for their expanding presence.

Saltwater crocodiles are highly territorial, she explained. Large males often force smaller individuals to disperse in search of new or vacant territories, while females become particularly aggressive during the nesting period. This territorial pressure, combined with changes in the landscape, pushes crocodiles into areas where they were previously uncommon.

“Organic waste disposal needs to be controlled near creeks and mangroves,” Oommen said. “Islanders did dump waste this way earlier too, but crocodile numbers were much lower, and the scale of dumping was limited because there were fewer locals and tourists.”

She added that crocodile movement becomes easier during periods of heavy rainfall and flash floods, when larger areas are inundated. “During such times, they can stray into locations close to human settlements. Nutrient-rich areas such as the mouths of creeks and streams, where fish and other prey congregate, also become particularly attractive.”

When Waters Rise

Shifting rainfall patterns have further amplified this movement. Heavier spells of rain cause creek systems to overflow, temporarily linking smaller streams, drains and even flooded village roads. These conditions allow crocodiles to access areas they could not reach earlier.

Flash floods triggered by erratic monsoons and cyclones can also displace crocodiles from their usual habitats, pushing them towards calmer waters closer to settlements. As creeks spill over their banks, the physical boundaries between waterways and villages blur, increasing the likelihood of encounters with people.

A 2024 study found that the highest number of human-crocodile conflict incidents and sightings were recorded during the wet season, between June and December, with nearly half of the encounters occurring at creeks. The study documented a sharp rise in sightings—from just three in 2015 to 23 in 2016—an eightfold increase within a year. Since then, sightings have remained consistently in double digits. Manglutan nallah recorded the highest number of sightings in South Andaman, with the Guptapara nallah ranking fourth.

Official records, however, present a more limited picture of harm. Government data shows eight crocodile attacks across the Andaman and Nicobar Islands between 2020 and 2025, only two of them in South Andaman and none reported from Guptapara. Livestock losses are also low on record, with three cattle attacks documented across the islands, two of them in South Andaman.

Ground surveys conducted between 2020 and 2023 suggest a wider gap between official records and lived experience. Researchers documented several attacks that went unreported. By 2023, six attacks had been recorded across the Middle and South Andaman region, four of them concentrated in the Guptapara–Manglutan stretch alone.

“I stopped fishing in 1999,” said Kumud Ranjan Saojal (63), a fisherman-turned-shopkeeper in Guptapara. “But when I used to fish, neither were crocodiles seen here nor did the area flood. Now, both happen together.”

Residents say changes in rainfall patterns over the years have reshaped life in the islands. In South Andaman district, overall rainfall increased by about 20% between 2020 and 2024, despite year-to-year fluctuations. In 2025, the southwest monsoon arrived earlier than usual over the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. The India Meteorological Department recorded rainfall at over 104% of the Long Period Average for the country, with the monsoon core zone receiving more than 106% of its average rainfall.

Climate models warn that such shifts are likely to intensify. The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report flagged small islands as especially vulnerable to flash floods caused by erratic rainfall and stronger cyclones. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands fall within India’s very high cyclone damage risk zone, with wind speeds of up to 55 metres per second. Cyclone occurrences in the region have increased in recent years, nearly doubling from around five annually in 2020. A 2015 study had already identified Guptapara as highly vulnerable to flooding due to cyclonic storm surges.

As climate unpredictability worsens, villagers say they are grappling with two overlapping threats: rising waters and rising crocodile encounters. Local leaders believe that reviving a long-abandoned water project could help manage both.

A Long-Delayed Dam

Construction of the Guptapara Nallah Dam began in 1992-93 as an alternative to the islands’ primary water source, the Dhanikhari Dam. The project was later stalled due to technological limitations. Over the years, silt and gravel accumulated in the stream, reducing its depth and capacity.

“The stream needs to be desilted…only then can the water level be controlled,” said Prakash Adhikari, Adhyaksh of the Zilla Parishad, South Andaman. “A crocodile was even captured at the Guptapara junction during flooding. They are now regularly seen near the playground close to the police station. It is during floods that crocodiles come up. If the dam is completed, water can be regulated and even stored for the summer. The recent floods happened because of neglect.”

The administration accepted Adhikari’s plea, and the Andaman Public Works Department (APWD) has since revived the proposal.

“This dam has the potential to work as a good reservoir,” said T.K. Prijith Rekh, Chief Engineer of APWD. “If built in such a catchment area, water can be released in a controlled manner during heavy rains. We are waiting for paperwork and the memorandum of understanding to be finalised, after which work can begin. Even though desilting is not formally part of our mandate, we will carry it out.”

Flash floods have not been limited to South Andaman. In recent months, visuals from Diglipur, Swaraj Dweep (Havelock) and Car Nicobar have circulated widely on social media. Rekh attributed these floods to a combination of erratic rainfall, cyclones and unplanned construction near creeks. He cited Mannarghat village, close to the crocodile-frequented Wright Myo Creek, as a recent example.

Coexistence

“Coexistence is the only way forward,” said Sanjay Kumar Sinha, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests. “We face immense pressure from the Centre. In February, I issued a killing order—the first in the islands—and was questioned extensively. There was strong insistence on capturing rather than killing the animal. The best approach is to respect the crocodile, understand its behaviour and remain alert.”

At Kumud’s shop, fishermen often gather to wait out the rain. Their conversations drift between expiring fishing licences, thoughts of leaving the profession altogether, and reports of yet another crocodile sighting nearby.

“In the Andamans,” Kumud said with a laugh, offering paan, “the life of a crocodile has value, not the life of humans.”

While men are statistically more likely to be victims of crocodile attacks, women in affected families continue to live with the fear that lingers long after an incident.

“Before the attack, my father used to fish morning and night,” said a woman whose family member survived a crocodile attack several years ago. “Now he is bedridden. Earlier, everyone in the village went fishing. After his leg was injured, I don’t let my sons or husband go. One man in the house is already confined to the bed—what if it happens again? I stay home more now because the others have to go out to earn.”

Others say they have learned to adapt.

“The crocodile stays in the creek; we stay on higher ground,” said Mohamaya Saojal (59). “Earlier, around 2017 or 2018, there was a lot of fear. Now, after living with this for so many years, we have become used to it. It doesn’t affect us as much anymore.”

Leesha K Nair is a freelance journalist and a member of 101Reporters, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.